When Niger formally declared Hausa its official language, the announcement may have gone unnoticed by many Western policy analysts who focus more on coups and sanctions. But make no mistake—this decision is not just a footnote in Niger’s politics. It represents a tectonic shift in the postcolonial African order.

What is Hausa? More Than Just Words

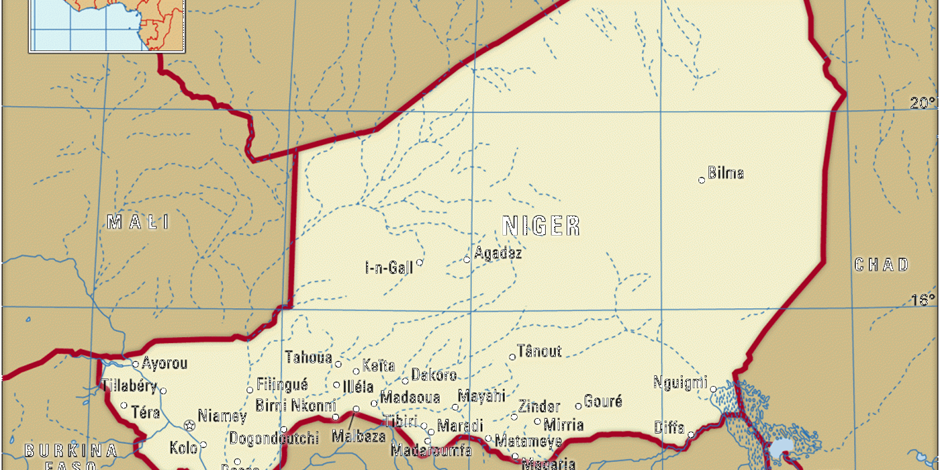

Hausa is a Chadic language. Part of the language group spoken across parts of Nigeria, Niger, Chad, and Cameroon that belongs to the broader Afro-Asiatic family (the same ancient language family that includes Arabic, Hebrew, and Amharic). It’s the most widely spoken language within the Chadic branch. Primarily used by the Hausa people in northern Nigeria and parts of Niger, Ghana, Cameroon, Benin, and Togo, as well as in Sudan.

Beyond being a local language, Hausa serves as a lingua franca. This common language allows different ethnic groups across West and Central Africa to communicate with each other, much like Swahili does in East Africa.

Key Features of Hausa:

- Tonal Language: Like Chinese or Yoruba, the pitch or musical tone used when speaking can change a word’s meaning completely.

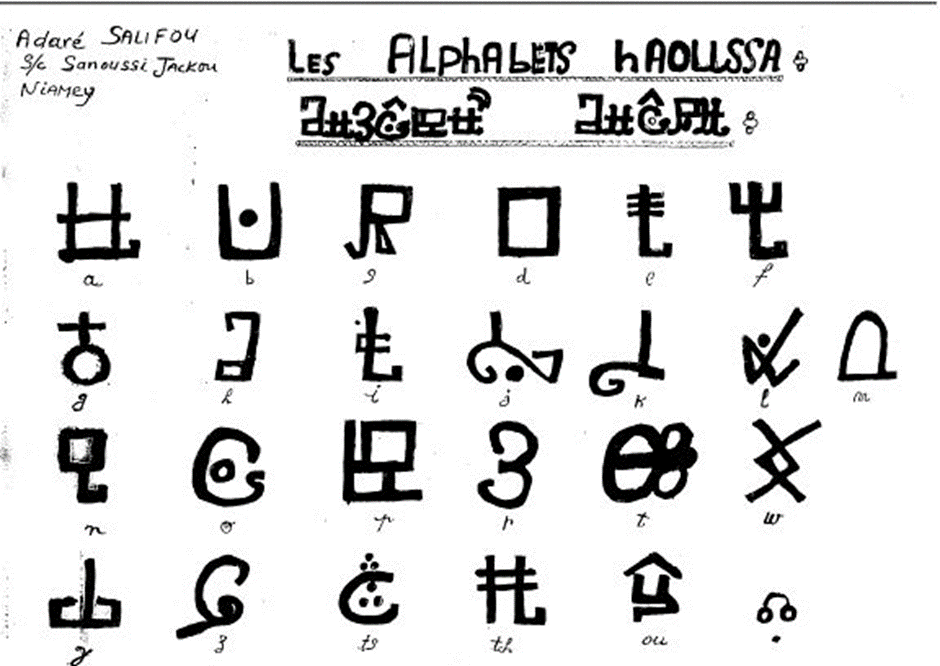

- Multiple Scripts: Hausa can be written in Roman letters (what you’re reading now) and Arabic script (called Ajami), connecting it to Western and Islamic intellectual traditions.

- Broad Reach: With over 80 million speakers, Hausa has substantial radio broadcasts, literature, and film industries, especially Nigeria’s growing “Kannywood.

- Growing Influence: Niger has recently adopted Hausa as its national working language, replacing French. This is the most significant shift away from its colonial linguistic inheritance.

I. Global Trends and Historical Backdrop: Deconstructing the Colonial Lingua Franca

Since independence, most African states have maintained the languages of their colonial rulers—English, French, Portuguese—not out of love but out of necessity. These languages were seen as gateways to global diplomacy, international aid, and maintaining elite status among our Narcoqueens and Godfathers.

Yet Niger’s move aligns with a broader global trend toward linguistic nationalism:

- In Latin America, indigenous languages like Quechua and Aymara have gained constitutional recognition.

- In Asia, countries like China, Iran, and Saudi Arabia have strengthened native-language governance while maintaining global relevance.

- In Africa, the promotion of Swahili in East Africa and Rwanda’s shift from French to English indicates a rising desire for linguistic realignment.

Niger’s adoption of Hausa represents a deep civilisational memory—resurrecting a language that predates colonialism. A mother tongue that sustained empires long before European powers scrambled for Africa. It is a symbolic rejection of neocolonial dependence, especially when French influence in West Africa sharply declines.

II. The Merits: Cultural Legitimacy, Regional Diplomacy, and Internal Cohesion

1. Cultural Legitimacy and Identity Politics

By formalising Hausa, Niger roots governance in its sociocultural soil. Over 60% of its population already speaks Hausa. This shift enables broader civic participation, improves bureaucratic inclusivity, and makes the state linguistically legible to its people.

2. Regional Integration and Diplomacy

Hausa is not confined to Niger. It is widely spoken in Nigeria (Africa’s largest economy) and parts of Ghana, Benin, Cameroon, and Sudan. Elevating Hausa aligns Niger with a transnational linguistic bloc, potentially giving rise to a West African “soft power corridor.”

In an era of Afro-regionalism, this could serve as a cultural counterweight to Western diplomatic dependency, offering new platforms for regional integration beyond ECOWAS.

3. Political Symbolism and National Unity

Amid military-led transitions and shifting alliances, Niger’s linguistic pivot signals a new form of nationalism: one that is rooted in indigenous legitimacy rather than inherited colonial structures. This may galvanise domestic pride and foster a unifying national narrative in a politically fragile state.

III. The Demerits: Global Isolation, Administrative Hurdles, and Identity Risk

1. Risk of International Disconnect

French remains the lingua franca of multilateral institutions, development banks, and various regional blocs. Though Hausa is rich in oral and cultural traditions, it lacks the institutional infrastructure—such as legal terminology, scientific lexicons, and diplomatic equivalents—necessary for comprehensive governance.

Translation gaps could hamper Niger’s engagement with global funding partners unless robust linguistic development initiatives are rapidly instituted.

2. Administrative and Educational Transition Challenges

Developing official documentation, training civil servants, rewriting curricula, and standardising legal frameworks in Hausa will require massive investment. This could lead to bureaucratic confusion, educational inequality, and transitional inefficiencies without careful rollout.

3. Exclusion of Non-Hausa Minorities

Although Hausa is dominant, Niger is home to over 20 ethnic groups, including the Zarma-Songhai, Tuareg, and Fulani populations. Prioritising one language risks reigniting ethnic tensions unless it is accompanied by inclusive policies that respect minority linguistic rights.

This is the paradox of all national languages: depending on the politics of implementation, they unify and divide, empower and marginalise.

IV. A Multipolar Future Demands Multipolar Languages

In the context of a shifting global order—with BRICS expanding and China and Russia rising– Niger’s Hausa policy could signal the early signs of linguistic decolonisation, particularly in light of the decline of Western hegemony.

Just as Mandarin, Hindi, and Arabic have become vehicles of influence, African languages must also evolve into tools of modern power—not merely relics of tradition. If supported by digital infrastructure, AI translation systems, education reform, and cultural production (think Hausa-language policy journals or film diplomacy), Hausa could help shape an African-centered global dialogue.

But this requires foresight. Language is not just about communication—it is the architecture of power, the software of sovereignty, and the soul of a nation.

Tiger’s Roar: When Our Words Become Our Weapons

Let’s be brutally honest: Africa has been independent on paper for decades, yet our minds remain colonised in borrowed languages. We draft our futures using someone else’s alphabet, articulating our dreams in tongues that struggle to pronounce our ancestors’ names.

Niger’s move isn’t just bold; it’s necessary. What is sovereignty if you must translate your deepest thoughts before expressing them in your parliament? What is independence if your legal system functions in a language that most citizens cannot understand?

The colonial powers understood exactly what they were doing when they imposed their languages upon us. Language is not neutral—it’s an operating system of control. Alter the language, alter the power structure.

So when Niger chooses Hausa, it’s not just changing words—it’s rewiring who gets to participate in governance, whose knowledge matters, whose wisdom counts.

Let the technocrats and Western consultants wring their hands about “global isolation.” Which isolation is more dangerous—being occasionally misunderstood in global forums or being permanently disconnected from your people?

Niger has chosen. The question is: When will the rest of us find the courage to speak our truth in our own words?

About the Author

Tiger Rifkin is a Pan-African writer, strategist, and communications consultant focused on geopolitics, ESG storytelling, and cultural sovereignty. He founded The Witty Observer, a platform known for bold satire and profound insight into African affairs.